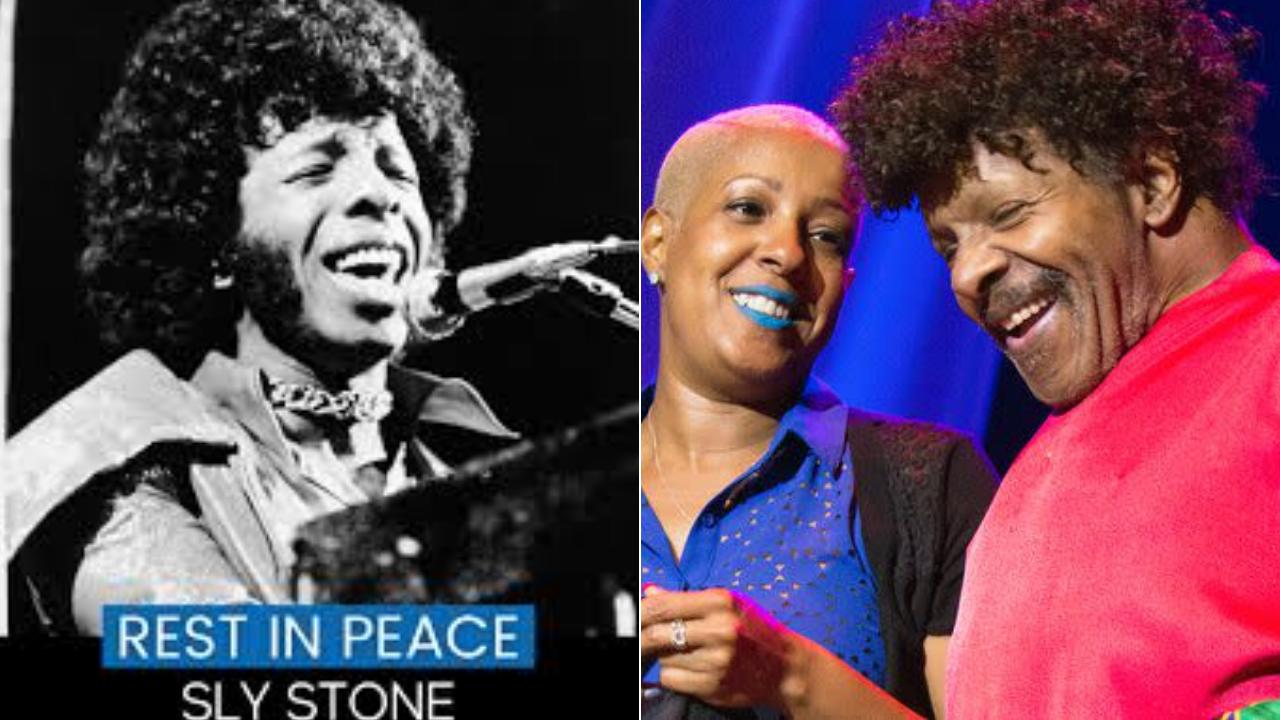

In a shocking and surreal turn of events, just thirty minutes ago, the world lost one of its most enigmatic and electric figures in music history: Sly Stone. The man who made the world “Dance to the Music” has taken his final bow, surrounded by close family — and the first words to surface came not from a press agent, nor a label, but from his daughter, who stunned fans with a brutal yet beautiful truth: “You know, we’re not sad. Maybe this is joy, because we helped our dad escape his physical pain and leave this world peacefully.”

The internet immediately lit up like a bonfire. Was it a loving farewell or a cold dissection of death? Within minutes, social media erupted — hashtags like #RestInPowerSly and #SlyStoneGoneTooSoon trended globally, even as fans and critics clashed over her statement. “She sounded so heartless,” one Twitter user snapped. “But maybe that’s what real love looks like when someone you admire has been suffering behind closed doors for too long.”

Sources close to the family claim Sly had been battling intense physical pain for years, exacerbated by chronic illness, untreated mental health struggles, and years of substance abuse. His body, once lean and kinetic, had reportedly grown frail and stiff — his voice, that unmistakable funk-stained growl, reduced to whispers. “He’d become a ghost in his own life,” one longtime collaborator told The Scoop under the condition of anonymity. “But that man never stopped feeling the music. Even in silence, his fingers twitched like they were playing bass.”

And while the world may now be mourning him as a legend, those inside the industry say there was a bitter undercurrent behind the scenes. Rumors are now surfacing that, in the last six months of his life, Sly was preparing to sue a major record label over unpaid royalties — a legal battle he never got to finish. Some say the stress from the case accelerated his decline. Others whisper that his inner circle pushed him to settle, fearing he’d uncover even more dirt on the music industry’s treatment of Black artists in the ’70s and ’80s.

“This man was robbed,” said a former agent. “He made millions dance, but he died with barely a penny. That’s the real tragedy.”

Sly’s career, of course, wasn’t just about music — it was about mythology. Rising to fame in the late 1960s, he broke boundaries with his racially integrated, gender-diverse band, Sly and the Family Stone. Hits like “Everyday People,” “Family Affair,” and “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” weren’t just songs — they were social manifestos wrapped in groove. But fame came fast and hard, and so did the demons. By the early 1980s, his erratic behavior, fueled by heavy drug use and increasing paranoia, had made him more ghost than genius.

“Working with Sly was like trying to hold on to a lightning bolt,” said a former bandmate. “Brilliant one minute. Vanished the next.”

Perhaps most heartbreakingly, his decline was often ridiculed more than it was respected. In the 2000s, stories of his homelessness — living in a van in L.A. — made headlines. In interviews, he was often visibly confused, but his flashes of clarity were haunting. “They forgot me,” he once said. “But I never forgot the music.”

But behind the scenes, things weren’t always so quiet. A source close to his daughter claims that even in his final months, Stone was writing, sketching, dreaming up concepts for a final album he hoped to call Exit Funk. “He wanted it to be his goodbye,” the source said. “But he didn’t get the time. Or maybe he gave it away.”

Some reports now suggest that unreleased material may surface soon — potentially a goldmine of tracks written during his reclusive years. Record labels are already circling, with one insider describing the race to secure rights as “a frenzy.” But fans are calling for caution, demanding that any release be “respectful” and “authentic,” fearing a posthumous cash grab like those seen with Prince and Michael Jackson.

And then there’s the celebrity drama. Allegedly, Sly had cut ties with several high-profile artists who once idolized him. Questlove, a known fan and historian of funk, was said to have tried multiple times to interview or collaborate with Stone in the last decade — but was consistently turned away. Some say it was pride. Others believe Sly distrusted most of the industry by the end. “He thought everyone wanted a piece of him, but no one wanted him,” one confidant said. “Can you blame him?”

Meanwhile, a major pop star — unnamed, but widely speculated to be Bruno Mars — reportedly tried to buy one of Sly’s old tracks to sample, only to be publicly rejected. “Funk ain’t for sale,” Sly allegedly told a friend. That phrase is now being printed on tribute t-shirts as the newest viral catchphrase among fans.

Outside his modest home in L.A., mourners have created a growing shrine: vinyl records stacked like altars, flowers in neon colors, graffiti that reads “Stay Funky Forever.” Some fans are even camping out overnight, playing his music on loop, holding impromptu dance vigils. “He brought the funk to the streets — now we’re bringing it back to him,” said one teary-eyed fan in platform shoes and an Afro wig.

Even his death has inspired a sort of chaotic celebration. It’s not grief. It’s gratitude. It’s not silence. It’s soul. And perhaps that’s exactly how Sly would have wanted it. No neat ending. No tidy legacy. Just noise, color, and that eternal, unstoppable rhythm.

And if you listen closely tonight — somewhere between the static and the stars — you might just hear it. That unmistakable groove. That voice that said what we were all thinking. That sound that refused to be forgotten.